Adriana Gutierrez*, September 21st 2021

“‘How long have you been renting?’ ‘ All my life’

“‘How long have you been renting?’ ‘ All my life’

In order to achieve people's integral development as individuals, human beings needs

to live in habitats to scale: the home,the neighbourhood and the town/city. So their habitat includes the house [and everything inside it], the environment [the neighbourhood around

the house],and the city. Such that the habitat comprises the dwelling and its surroundings."

(Giraldo Isaza, 1993).

Nicaragua's legal framework has enabled the Government of Reconciliation and National Unity (GRUN) to define, in its National Human Development Plan, the main threads of public policy on property issues integrating families into their housing, their community and neighbourhood or district, all within an inclusive urbanization.

Article 4 of the Constitution states: "The Nicaraguan State recognises the person, the family and the community as the origin and the objective of its activity, organised to ensure the common good...". Likewises Art 64 states that: "Nicaraguans have the right to decent, comfortable and secure housing that guarantees family privacy. The State shall promote the realisation of this right."

In addition, special Law 677 passed in 2009 promotes house building and access to social housing. This was a milestone in formulating public policies addressing social problems like the housing deficit. In 2014, the authorities reckoned that Nicaragua has a housing deficit affecting 957,000 people in a country of 6.4 million. Since then far from being reduced or stopped the deficit has continued to grow.

In 2021, the GRUN put in place a National Poverty Reduction Plan 2022-2026, which links the issues of property and access to housing. The plan refers to "inclusive, healthy, creative, safe, resilient and sustainable cities, urban districts and villages, and the guarantee of property rights in cities and in the countryside". This implies two lines of action

1. Guaranteeing the legal security of property titles.

To this end, the property regulation and remediation process will continue, assuming the costs of mass emission of property titles free of charge. Since 2007, the GRUN has issued more than 500,380 property titles. This historical fact sets a standard for the country's development, and has been made possible thanks to the creation of mechanisms incorporating all the state institutions that make up what is known as the Property Road Map.

Likewise, with the creation of the SIICAR-2 Integrated Cadastral Registry Information System, the basis for the construction of a modern multi-objective Land Registry was established, which not only makes possible an updated inventory of properties, but also greater protection of private and public assets, as well as real-time access to cadastral and land registry information, for the State and the general public.

2. Carry out programmes offering decent family housing and housing developments, through a multi-sector Alliance Model bringing together different key actors to promote access to housing: Government, Municipalities, Private Sector, Financial Sector, Developers, NGOs, Workers and International Cooperation.

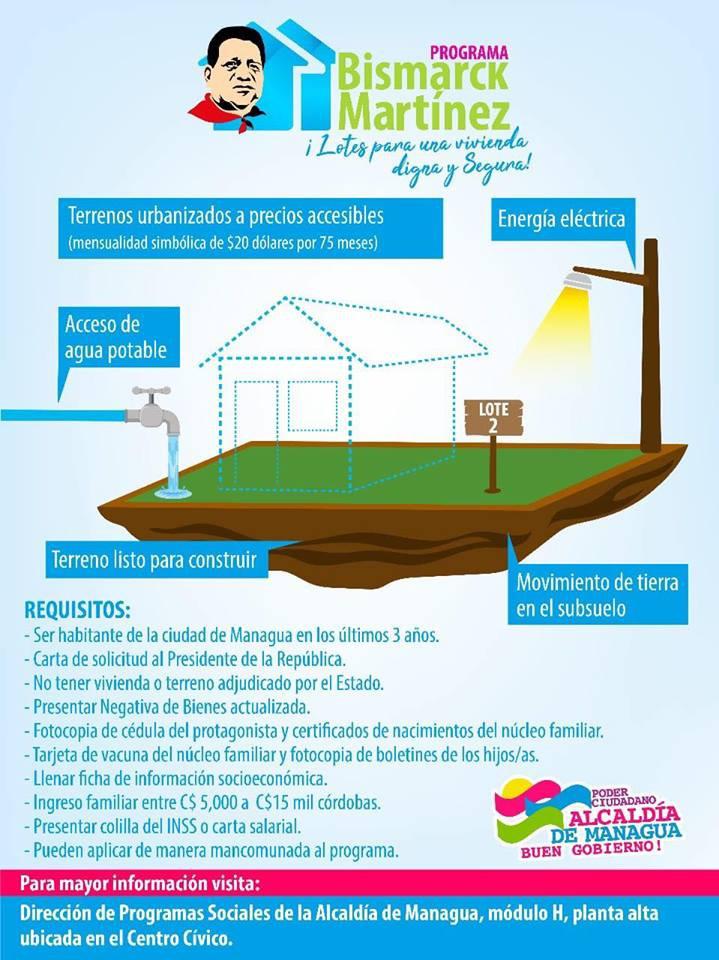

Among the multiple projects being developed, the Bismarck Martinez Programme is emerging as the largest, most comprehensive and emblematic; the programmes' largest projects will be implemented in Managua. Over time Managua has grown in a chaotic way as a spontaneous response to people’s needs in space and time. In 1992 the architect Ninette Morales Ortega carried out research work on "The Nicaraguan popular habitat: taking over urban land", where she states that the categorization of the neighbourhoods in Managua is determined by the way in which people acquired the land.

The first category is that of spontaneous human settlements, which are the result of illegal takeovers of abandoned land, and where there are no recreational areas or streets.

The second category is that of unauthorized urbanisations or popular neighbourhoods, which are the result of the informal land use market, i.e. an owner divides his/her land into plots and sells them, but without any planning or notification to the municpal authority; there are no recreational areas, but there are streets.

And the third category are those progressive neighbourhoods, where the government has legally divided land into plots and planned the areas; there are recreational areas and streets, but few inhabitants because not all of them have basic services.

In the 1980s, the government of the Sandinista Popular Revolution, divided vacant spaces into lots and designed an urban plan that included recreational areas, thus creating progressive urbanisations.

The areas in green are where the State intervened during the 1980s. The red areas are land occupations between 1990 and 1995.

Weber's concept of the city, in which power facilitates the construction of society and the individual, was put into practice with the process of social dynamics that took place in the 1980s. Social movements and the government's political structures set about creating a new city designed and built by its inhabitants. This was only possible through citizen empowerment, which is one of the greatest legacies of the revolutionary process.

In 2018, amidst the latent socio-political crisis, as one might expect, people sought "their own answer" to the housing problems that affected them so much. A large mass of citizens rushed to find picks, shovels and builders line: they were going to take over the land; some out of need, others in order to speculate, but all out of necessity.

In tens and then in hundreds, they went to the areas like the Suburbana, Carretera Nueva León, Mateare, or Sabana Grande; looking either for land they believed belonged to the State or for private land they knew had been idle or vacant for decades.

The whole process happened very quickly. I understand that in other towns around the country there were also takeovers, but I only experienced the ones that happened in Managua. In a matter of days, they had already divided up and even built structures on the land, within a week they were selling the plots at between 5,000 to 10,000 thousand córdobas. Bingo!

The informal land dealers in Nicaragua have no scruples in profiting from people's needs and dreams. And so, with no documents, nor legal security, with nothing to back them up but their hope, many people got into debt or handed over their savings to these swindlers.

Everything suggested that history was going to repeat itself, but this time it was different. Local government had the political and institutional capacity to manage the crisis and break up the massive seizure of multiple properties. In an inter-institutional effort, the Mayor's Office of Managua achieved a historic milestone of massive, orderly eviction with few incidents, as well as imposing its authority as the regulator of the city's urban development processes.

In two weeks everything was dismantled, and nothing was left of the improvised structures of black plastic, galvanized roof sheets, nothing but the lines on the ground setting ut what never came to pass. And the big question was what now? What do you do as a Municipal Authority when all the numbers and statistics have become faces, names, ID cards, people sobbing and lists; what do you do when the problem can no longer be brushed under the carpet?

If we had had a neoliberal government, I am sure they would have bought a bigger carpet, but in the last elections we were lucky enough to make the right choice and we have a Sandinista government!

The central government, together with the local governments, showed their political will and decided to redouble their efforts in the providing access to decent housing: thus the Bismarck Martinez Programme was born.

In its first stage, it was projected as a plan to divide the land into plots with an installment payment mechanism for the purchase of the land.

Months went by and the first pilot initiatives were put in place in Managua and other towns and cities, but something happened: the authorities realised that land was not enough, that the quality of life of the program participants was not going to improve if all the necessary conditions were not created.

It was evident that the decision makers reached the same conclusion as the theoreticians: Nicaraguans need a place in which they can develop in an integrated "habitat that corresponds to housing plus the environment" (Giraldo Isaza, 1993). Hence, there is no habitat when you have a house without an environment or an environment without housing. Setting out lots is not enough, housing is needed.

The Bismarck Martinez Programme proposes building 50,000 houses throughout the country, of which 20,000 will be in Managua; this represents the first urban project of this magnitude in the history of Nicaragua integrating all the necessary components to create a decent, efficient and above all individually owned.

In Point 10 of the National Poverty Reduction Plan for the period 2022 - 2026, the GRUN sets out with political clarity direct action to attack the roots of poverty, because the programmes enables via access to decent housing and investments, the basic material conditions in which Nicaraguans will be born, grow and live, ensuring they will be able to realize their integral development.

In summary, in terms of housing and legal security, this axis proposes: people will get houses which will belong to them.

This programme is not just a bunch of little houses set apart, it includes an Urban Master Plan that includes the planning, infrastructure and urban facilities necessary to satisfy a demand for housing that undeniably continues to grow as a result of historical inertia.

Roads, streets, pavements, drinking water systems, a mains sewage and drainage system, public lighting and electricity networks, municipal citizen service centres, police stations, health centres, schools, parks, public urban transport, waste disposal, community areas, green spaces, among other things allow a high level of satisfaction of basic needs, as well as offering the conditions for families who live in these houses to have a quality environment.

To date, 1,500 homes have been handed over to people who are protagonists of Bismarck Martinez, and I am one of them. There is already a flourishing economic dynamic: a tortilla stall, a grocery store, a tailor, a welder, street food sellers, a hardware store, a beauty salon, among others.

The inhabitants are organized and currently there are three Public Bus Routes: 110, 120 and 159. We are 10 minutes away from the Mercado Mayoreo, connected to the rest of the city by different roads. We all have electricity and drinking water, our houses all have electricity, drinking water and mains sewage. They are equipped with a toilet, bathroom and a laundry room, the plots are 150m², but some are larger for those who can pay more.

In the last decade, taking advantage of the model of alliances promoted by GRUN, private developers have begun to offer "social interest housing developments", with the objective of benefiting from the subsidies guaranteed under the housing law; however, housing costs and high profit margins made it impossible for people with less than three minimum wages to apply.

To achieve their objectives, they offered buildings of up to 38m² or 42 m², costing US$20,000 or more and with financing that meant monthly repayment instalments of US$180 or more. They claimed this included finished floors and walls, ceilings and internal partitions. But what was the quality of those materials? How much did they save on measurements such as "party walls" between two homes? All of which meant that they shortchanged the owners of the property.

On the other hand, it is public knowledge that these urbanizations have a series of problems such as being subject to flooding, or non-compliance with the technical requirements for septic tanks or constant problems with the drinking water pumps, which have left their inhabitants for weeks at a time without this vital service. Also being designed according to an urban logic of segmentation, this means there is no connection with the rest of the urban fabric. There are no public bus routes meaning people have to walk long distances or use taxis or hired vehicles that increase their transportation costs and limit their mobility.

It is also necessary to understand that "The action of inhabiting goes far beyond using, occupying, settling in, protecting oneself under, since the dynamic process of inhabiting results from the confluence of different worlds: natural, social, economic, cultural, emotional, physical-spatial. By inhabiting, the human person expresses that they are building their place, territory and life system in order to identify with them, to feel them as their own and at the same time to belong to them, to take root there and, similarly, to project ehmselves from there. Therefore, inhabiting does not only have a spatial meaning, but a multidimensional meaning because by inhabiting, the inhabitant establishes connections with all the components of their environment, uses them, transforms them and therefore, inhabits them at different levels, feeling that he belongs there and participating in their transformation and development." (Chardon, 2010)

The property market has caused an increase in land values in various parts of the capital, however, this speculation has not been sustainable because it was driven by the economic interests of investors specialized in turning housing which should be a right into a commodity.

Our houses measure 54m square metres , each one costs approximately US$13,228.28, of that amount the Institute for Rural and Urban Housing (INVUR) subsidized 23%, the Municipal Authority subsidized 24% on top of what I had already paid, which reduced the purchase price to less than half. With that purchase price agreed, through the programme I was able to borrow money from a bank which I am paying off in monthly instalments of US$50. And this is how I have been able to claim my own and my daughter's right to have our own home.

One of the requirements to apply for this programme is not to have any property registered in your name. This means that most of the programme participants were either living in other people's houses or renting. I had moved ten times and rented for seven years of my life, which means that I had already paid out $12,600 in rent alone, there are people who spend their whole life renting.

When I went to see my house, my daughter asked me: - Mom, are we moving again? -I answered, "Yes, but this is the last time we're moving”, because this house was already hers, and mine, OURS!

The programme is located in Sabana Grande, a historically rural area with land use designated for agriculture. With the construction of the Sabana Grande-Esquipulas highway, a change in land use began. In addition, all the infrastructure and urban facilities being installed will generate a considerable change in capital gains, currently one square metre of undeveloped land may cost between US$6 and US$8. Once urbanized it will cost much more.

The Bismarck Martinez Programme also addresses another direct aspect in the quality of life: legal security. As I mentioned before, in Managua for decades there have been spontaneous human land settlements, one of the key characteristics of this urban category is that the land does not legally belong to the people settling them and this has economic and emotional repercussions.

Currently with commercial housing developments the developers are the registered owners of the parent plots, and it is not until the debt is paid off that the buyers can proceed with registering their property. The costs of registering a property are high, many people take years to regularize their property, while others never do.

Under the Bismarck Martinez Programme, all programme participants will be the registered owners of our plots, at no cost; the emotional and economic consequences of knowing that you own the land you walk on and the house you live in, are an investment in a fairer society, in which thousands of children like my daughter will grow up with stability.

* Adriana Gutiérrez is an architect

References

Chardon, A.-C. (November 2010). “Resettling a vulnerable habitat: theory versus practice.” Revista INVI, 25 (70).

Giraldo Isaza, F. (1993). “Towards a new concept of housing and urban development”

Síntesis del trabajo Necesidades Habitacionales, Informe para el Gerente General del INURBE presentado por el CENAC Bogotá. Bogota: INURBE.

Ortega, N. M. (diciembre de 2012). Mercados Informales de Suelo y Regularización de Asentamientos Humanos. Managua, Nicaragua. No internet link found.